At the most recent Executive Board meeting in Going, Austria, the International Biathlon Union voted to discontinue blood testing as part of antidoping efforts at all future Olympic Games.

“Based on the experience of the last two Olympic Winter Game editions for which the IOC has sole testing authority, the IBU EB decided: In the future the IBU will conduct no own blood screens at OWG, but assist the IOC [International Olympic Committee] with expert advice for their test plan,” read the minutes of the Executive Board meeting, which were given to FasterSkier by three separate sources.

No further explanation has been given to the federations regarding the reasoning behind the decision, and IBU President Anders Besseberg has not responded to FasterSkier’s requests for comment. However, internal Executive Board documents show that IBU Secretary General Nicole Resch advocated for the change in her presentation to the board.

The IOC is responsible for much of the antidoping testing at the Olympic Games. In Sochi this winter, the IOC administered over 2,400 tests across all sports. At first blush, this would indicate that the additional independent testing done by individual sports federations may be redundant.

At issue, however, are blood tests which are used for Athlete Biological Passport (ABP) programs, a scheme which tracks levels of different markers in athletes’ blood over many years. This allows medical administrators to detect spikes in oxygen-carrying capacity or other physiological parameters which may be due to prohibited substances for which there is no analytical test.

The ABP model was developed by WADA and adopted by its Executive Board in 2009. The blood “module” of the ABP has been approved by the Court of Arbitration for Sport, and the international federations for track and field and cycling have brought ABP cases to CAS.

The IBU uses several passport-type approaches in its blood tests.

“The first is to do a blood profile for the WADA blood passport,” IBU Vice President for Medical Issues Dr. Jim Carrabre told FasterSkier. “The second purpose is for our own internal program called Arietta, which allows us to identify athletes at higher risk for blood manipulation.”

The IBU also has a combined system of cutoff values for hemoglobin levels and the off-model score (hemoglobin value – 60√reticulocyte value) and does not allow athletes to start competitions when they are above both these cutoffs, but does not use this system at the Olympics.

The IBU has championed its passport program and its ability to target specific athletes for additional testing. This led to the suspension of Russian biathletes Irina Starykh and Ekaterina Iourieva this winter after targeted testing led to positive tests for recombinant erythropoietin, a common blood-doping drug.

Carrabre said that biological passport data belongs to the federations and that the IOC would not be able to catch athletes using this technique at the Olympic Games.

“We would grant them permission to have [the data] they wanted to have that,” Carrabre explained. “However, the IOC as a testing authority, the length of time at the Games, it’s not enough for them to develop a passport that is positive. Not enough time to get enough tests. So you will never see a positive passport come out of the [IOC at the] Olympic Games. It has to be from the federations.”

Dr. Arne Ljungqvist, the outgoing head of the IOC Medical Commission, confirmed that the ABP program has never led to a suspension at an Olympic Games. But he said that the IOC’s testing was sufficient. He explained that federations dropping “no-start” testing was a direction he urged to move in, and had discussed with Besseberg. However, Ljungqvist was not familiar with the IBU’s Arietta and ABP testing.

And inside a biathlon community which has seen four positive tests from World Cup athletes this past season, limiting the amount of testing done at the Olympics seemed to be a perplexing move. Nobody else contacted by FasterSkier had the same reaction as Ljungqvist, that this was a “logical step because of the WADA ABP.”

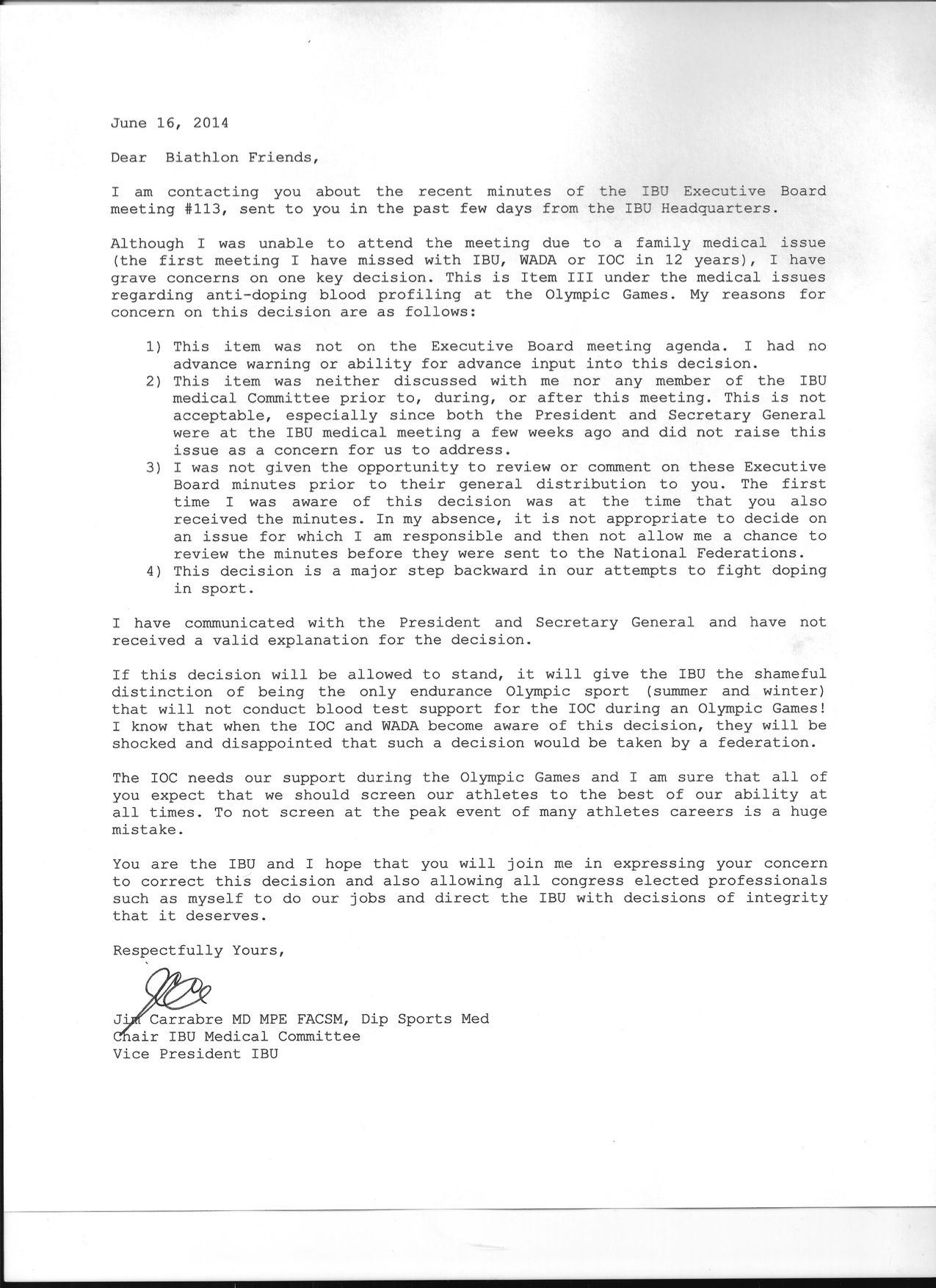

That begins with Carrabre. The IBU did not appear to have consulted its own medical committee, which is responsible not only for health of the athletes but also for antidoping work, before taking the decision. Carrabre was not present for the vote although he is a member of the Executive Board due to a family health emergency. A longtime antidoping advocate, Carrabre said that he was not contacted regarding the proposed change. He also said that Resch’s internal board memo was never sent to him, not even after the meeting.

Carrabre is running for the IBU Presidency this fall against incumbent Anders Besseberg of Norway, on a broad platform that includes, among other things, improving antidoping efforts and transparency.

Dr. Fabio Manfredini, an Italian doctor who is also a member of the medical committee, wrote in an e-mail to FasterSkier that he had no comments on the decision. Dr. Pierre Jeannier of France, another member of the committee, confirmed that the Executive Board had not sought his opinion, either.

“I am not sure that is a medical problem – as you probably know there is an important IBU Congress in September, and maybe there are some fights before this,” he wrote in an e-mail to FasterSkier. “I had no contact with any members of IBU board. Jim Carrabre is our chairman. He is VP for medical issues, and I trust him. For me the political problem is the main problem.”

However, as neither indicated that they had been contacted before or during the deliberations, it appears that the Executive Board excluded all medical committee opinions, not only those from Carrabre, the candidate against Besseberg for President.

“It just blew my mind,” Carrabre told FasterSkier. “Like, where did it come from? We had a Medical Committee meeting a few weeks before in Prague, and Anders Besseberg and [Secretary General] Nicole Resch were at that meeting and had a chance to discuss that topic if it was an issue for them.”

Adding to the confusion, the issue was not placed on the Executive Board agenda before the meeting. This was among the issues addressed by Carrabre in a letter that he sent to all of the national federations after he saw the decision in the minutes. According to Carrabre, he has still not been able to reach President Besseberg to discuss the reasoning and execution of the decision.

The whole board was not present for the vote. In addition to Carrabre’s absence, Vice President for Special Issues Nami Kim was not in attendance. Vice President for Development Václav Fiřtík died unexpectedly this spring, and his position has not yet been filled. That left seven of an intended ten-member voting body to decide the change. It is not clear which Executive Board member proposed the change.

The decision and its lack of explanation have left many members of the biathlon community confused.

“I am as mystified about that as anybody,” U.S. Biathlon Association CEO Max Cobb, who is the chair of the IBU’s Technical Committee but not a member of the Executive Board, told FasterSkier. “I obviously don’t understand it. I can tell you that the feedback that we had at the Games was that the nations really wanted blood testing and blood screening to be done at the Olympics, because it’s an integral part of IBU’s antidoping effort.”

Cobb said that the only way he could imagine this to be an appropriate decision was if some other body was taking over the testing responsibilities, but “that seems hard to imagine.”

Biathlon Canada High Performance Director Chris Lindsay also saw the decision in the Executive Board minutes, and said that while his organization has not yet contacted the IBU about the issue, Biathlon Canada is likely to do so because “there is some fallout from this Executive Board meeting that we have some concerns about.”

His was particularly interested in the fate of the Athlete Biological Passport program, which he said was important in ensuring clean sport.

“Biathlon Canada is a signatory to a Canadian program called True Sport… and while the process of testing for people who are trying to manipulate the system may be inconvenient, it is well-accepted and well-understood amongst everyone – the athletes, the coaches, and the officials in Biathlon Canada – that we need to do everything that we possibly can to support initiatives that insure clean sport,” Lindsay said. “And I would suggest that that is a primary driving force behind behind Biathlon Canada as we seek clarification on the decisions made by the Executive Board.”

Chelsea Little

Chelsea Little is FasterSkier's Editor-At-Large. A former racer at Ford Sayre, Dartmouth College and the Craftsbury Green Racing Project, she is a PhD candidate in aquatic ecology in the @Altermatt_lab at Eawag, the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology in Zurich, Switzerland. You can follow her on twitter @ChelskiLittle.